One of the most common reasons taxpayers seek out professional tax help surrounds the uncertainty of which state or state(s) they need to file in, and how to fill out those returns. The federal tax return is the same no matter where you are located, but each state return is unique with its own tax system that consists of different rules, calculation methods, and deductions. Advances in technology and an increasing popularity in remote work has thrown new wrinkles into the system. There are many avenues to explore with state taxation, but what I will focus on today is the situation most common to the majority of taxpayers: handling the reporting of their job compensation. Two of the most common questions asked are:

- What state should be on my W-2?

- What state do I pay state income tax to?

What state should be on my W-2?

In most situations, states will require an employer to withhold state income tax from the employee’s pay for the state that the job is located in. One exception to this rule are states with reciprocity agreements. When two states have a reciprocity agreement with one another, the employer is allowed to withhold for the state that the employee resides in. As of this writing, here are the states with reciprocity agreements:

| Work State | Residential State |

| D.C. | Maryland, Virginia |

| Illinois | Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Wisconsin |

| Indiana | Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin |

| Iowa | Illinois |

| Kentucky | Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin |

| Maryland | DC, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia |

| Michigan | Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Minnesota, Ohio, Wisconsin |

| Minnesota | Michigan, North Dakota |

| Montana | North Dakota |

| New Jersey | Pennsylvania |

| North Dakota | Minnesota, Montana |

| Ohio | Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Pennsylvania, West Virginia |

| Pennsylvania | Indiana, Maryland, New Jersey, Ohio, West Virginia, Virginia |

| Virginia | Kentucky, Maryland, DC, Pennsylvania, West Virginia |

| West Virginia | Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia |

| Wisconsin | Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan |

It’s important to note that the reciprocity agreements typically only cover employment income. This is income that is reported to you on a Form W-2. Any other form of income would not fall under the reciprocity agreement. Examples of income that is not subject to reciprocity agreements include income you make from your own business (reported on Schedule C) and income that is reported to you on a Form 1099-NEC (non-employee compensation).

For remote workers, in most situations, the employer should be withholding based on the physical location that the employee is working from, not the office location. If the employee moves during the year, they should inform the employer of the new state they are working from so the employer can change the withholding. One exception to this are the handful of states that have a “convenience of the employer” rule (discussed later). In those states, the employer should withhold based on the employee’s assigned office location.

What state do I pay state income tax to?

As of this writing, all states have laws that declare income is taxable in the state if the wages meets either of the following:

- Location-Based: Employee receives wages while residing in the state, or

- Sourcing-Based: Employee receives wages from a source within the state while not residing in the state.

For most taxpayers who live and work in the same state, this determination is simple. They report the income to the state that they live/work in. However, there are some unique situations that could lead to confusion, such as:

- Moving to a new state for a new job.

- Commuting across state lines for work

- Working remotely

Moving to a new state for a new job

Quick Answer: The wage is apportioned between the two states based on how many days/months you lived in each state.

Explanation: Let’s say a taxpayer worked and lived in North Carolina to begin the year. On June 20th, the taxpayer accepted a new job in a new state. They put their house on the market and moved into an apartment closer to their new job. The taxpayer moved into the apartment on July 5th and the job began on July 7th. In this situation, the taxpayer may be wondering the following:

I moved to an apartment before starting work but I still owned my old house in my old state. Which state am I considered to be residing in?

All states define residency if the taxpayer meets one of the following requirements:

- Intent-Based: The taxpayer establishes their domicile in the state.

- Measurable: The taxpayer spends a certain number of days or months in the state. The measurement method and precise number of days varies by state. However, this rule generally classifies a taxpayer as a non-resident if they spent more than half the year in the state, unless they abandoned domicile in the state.

In defining residency, all states use a term called “domicile”, which is a fancy word for your permanent home. When you rent or own multiple properties, determining your domicile is a subjective matter that attempts to answer “where is home”. Generally, the taxpayer should attempt to answer that question to determine their domicile. For a worker who travels a lot or who moves to a new state for school, their domicile doesn’t change while absent, even if it exceeds the measurable requirement, because there is an intend to return. However, in this situation, it’s clear that the intent is to not return. Therefore, the taxpayer establishes their new domicile and becomes a resident in the new state when they moved on July 5th. A taxpayer can only have one domicile at a time. Once the domicile is established, it does not change until there is evidence that the taxpayer has both:

- Established domicile in another state, and

- Abandoned domicile in the former state.

The date of July 5th should also be used in determining the apportionment of income. Because there were 180 days from July 5th to the end of the year, the taxpayer will apportion 49.3% of their annual wage to the new state (180 / 365). Because the taxpayer spent 185 days in the former state, they will apportion the remaining 50.7% to the former state (185 / 365).

For North Carolina, the measurable requirement uses a figure of 183 days. Notice that the taxpayer spent 185 days in Noth Carolina, 2 days more than the threshold. However, because the taxpayer both established domicile in another state, and abandoned their domicile in the former state, the number of days does not matter. The action of putting the house on the market is evidence of abandoning the former state’s residency.

Commuting to work across state lines

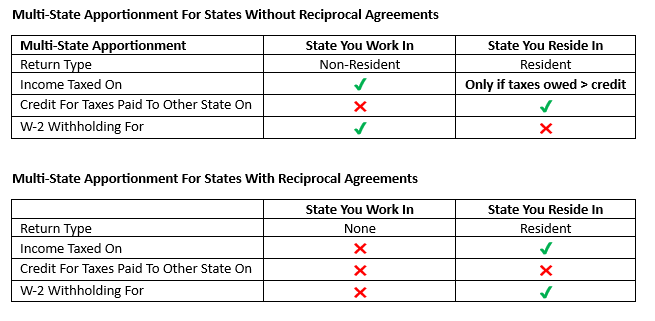

Quick Answer: Unless there is a reciprocity agreement between the two states, then the taxpayer files two returns: a resident return in their state of residency, and a non-resident return in the state they work in. The income will be shown on both returns, but only taxed at the highest tax rate between the two states. The taxpayer may owe to both states if the tax rate of the working state is lower than the tax rate of their residency state. If a reciprocity agreement exists, then the taxpayer will file one return for their residency state.

Explanation: Let’s say a taxpayer lives in North Carolina but commutes to South Carolina for work every working day and received $40,000 in wages. In this situation, the taxpayer may be wondering:

Do I pay tax in the state I live in or the state I work in?

Under the location based rule, the resident state of North Carolina has a claim to the entire amount of wage paid because the employee resided in the state all year. However, the working state of South Carolina also has a claim to the entire amount of wage paid because the employee worked in their state all year. Therefore, the income will go on both returns. However, the taxpayer will not be taxed twice on the income. All states give a credit on the residency return for taxes paid to another state. Therefore, the order of operation is to fill out the non-resident return first. Then carry the amount of tax paid on the non-resident return over as a credit on the resident return. If the tax rate for the resident state is higher than the tax rate of the working state, the credit may not cover all the taxes calculated on the resident state return. In this situation, the taxpayer will owe to both states, and the net effect will be that the income is taxed at the tax rate that is highest between the two states.

So in this situation, the taxpayer would list the entire wage amount on the South Carolina non-resident tax return and pay their rate (3.8% as of the time of writing). The total tax paid would then carry over as a credit on the North Carolina resident return. The taxpayer would also list the entire wage amount on the North Carolina resident return and calculate the tax owed (4.75% as of the time of writing). However, the credit for tax paid to South Carolina would reduce the amount owed, but not eliminate it. The taxpayer would pay North Carolina the difference of roughly 0.95% (4.75% – 3.8%). Note that in the opposite scenario, the resident state does NOT refund a difference. Rather, the taxpayer would simply not owe anything to the resident state.

The exception to this rule is if the two states have a reciprocity agreement. In that case, the taxpayer simply pretends as if they worked in the same state that they live in. They will file a resident return in the state they live in and pay the tax that is assessed in the resident state.

Working Remotely

Quick Answer: Unless the taxpayer works in one of the handful of “convenience of the employer” states, the taxpayer pays tax to the state they physically performed the work in. If they work in a convenience of the employer state, they pay tax to the state where their assigned office is physically located in, and follow the same process outlined in the previous commuting section.

Explanation: In recent years, remote work has exploded in popularity. This can cause taxpayer’s to be confused on which state to file in. In this situation, the taxpayer may be wondering:

I work in one state remotely but the office is in another state. Which state do I need to file in?

Like in the commuting section, the question of “does the income fall under either the location-based reporting requirement or the source-based reporting requirement” needs to be asked for each state separately. With the exception of a handful of states which are considered “convenience of the employer” states (discussed later), the source of the income is considered to be where the taxpayer was physically located when they performed the work. So if the taxpayer works remotely from home, then the income would meet both requirements and they would file only a resident return in the state they live/work in. They would not file in the state that the employer is located in.

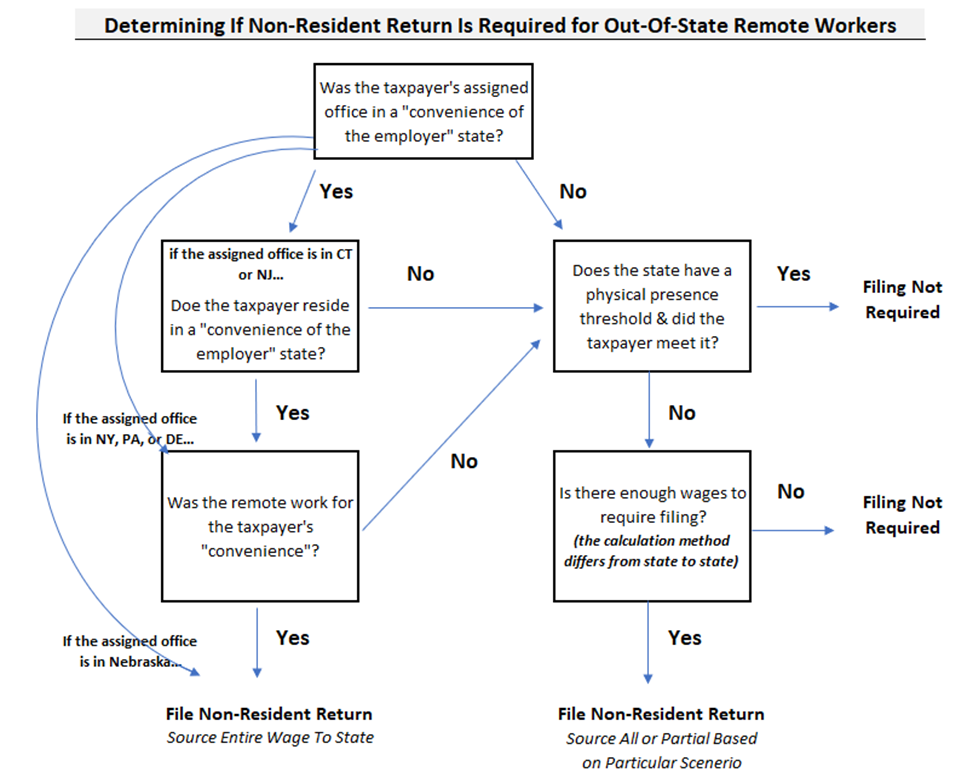

Let’s say that instead of working from their home all year, the taxpayer decided to travel around and sight see while working remotely. Consider this scenario: after accepting a remote position, the taxpayer does not renew their apartment lease and begins travelling around renting out Airbnb rooms for months at a time in different states. In that situation, we would first determine which state is the residency state (see previous discussion in the new state for new job section). The residency state is the state in which the taxpayer plans to return to once they have finished travelling. In situations where a taxpayer has no domicile, signs of connection such as where they receive mail, where their driver’s license is registered, the address used on the tax return, and any existing business or family ties should be considered. The taxpayer must have one resident state and cannot have more than one. Also keep in mind the measurable requirement. If a taxpayer stays in one state for more than half the year, they may meet the state threshold to automatically be considered a resident. Once the resident state is determined, whether they have a filing requirement in the non-resident state(s) depends on:

- Does the state have a threshold for number of days present before being required to file a non-resident return (physical presence test)?

- Did the taxpayer earn enough income while in the state to have a filing requirement?

- Is the employee’s assigned office located in one of the “convenience of the employer” states?

In a small number of states, you are allowed to be present in the state for a certain number of days before triggering a filing requirement. For example, beginning in 2024, you are not required to file a Montana non-resident return if you are present for less than 30 days. While there is a push in some states to pass similar physical presence laws, the large majority of state require the filing of a non-resident return if you spend just 1 day working from the state.

However, the lack of a physical presence test does not automatically mean the taxpayer has a filing requirement. Some states do not require a non-resident to file if the income they earned while working from the state does not meet a specific dollar amount. This filing threshold, and the method used to calculate whether a taxpayer meets it, varies from state to state. For instance, Arizona does not require a non-resident to file if the wage earned while in Arizona is below the Arizona standard deduction for their filing status. However, North Carolina requires the taxpayer considers their total wages for the year (not just NC apportioned wages) in determining whether their wages exceed the NC standard deduction for their filing status.

Finally, a taxpayer must consider whether the state is a “convenience of the employer” state, which could change the definition of “source within the state” under the source-based rule if their assigned office location is within one of these states. As of this writing, there are 6 states where this applies:

- New York

- Delaware

- Pennsylvania

- Connecticut: only applies if the residency state has the rule as well (retaliatory)

- New Jersey: only applies if the residency state has the rule as well (retaliatory)

- Nebraska: No “convenience” requirement, but rather outright instructs that the source should be considered based on the assigned office location. Recent state legislation has been proposed to remove this but has not passed as of this writing.

“Convenience of the employer” is a term referring to a law that is on the books of these states (except Nebraska) that potentially changes the definition of “source from within the state” under the source-based rule. Remember that without this rule, the source is the state the worker is located in when performing the work. Under this rule, if the worker is choosing to work remotely for their “convenience” rather than out of “necessity”, then the source changes to the location of the worker’s assigned office. While Nebraska is considered one of these states, it does not actually require a “convenience” determination, but rather outright requires all remote workers to consider the source as Nebraska. Additionally, because this law effectually reduces income tax revenue in surrounding states, Connecticut and New Jersey only apply the “convenience” rule if the taxpayer is residing in another “convenience” state (including Nebraska). The net effect is: for remote workers located out-of-state with their assigned office in these states, this has the effect of potentially requiring the filing of a non-resident return and sourcing all wages to the state under the source-based rule.

A taxpayer may be wondering “how do I determine if I’m working for convenience or necessity.” Since this is a state law, the wording, meaning, and interpretation varies from state to state. Taxpayers in these states should analyze instructions from the government agencies, rulings from the state/federal courts, and the sentiment among other taxpayers and tax professionals in coming to an educated conclusion. To provide some context on the law and its intent, it originated in New York to prevent office workers from working remote in a surrounding state to shift income out-of-state. New York takes a very hardline definition of “necessity”, recently ruling in Zelinsky vs. New York (2023) that even when New York offices were shut down by state order during the 2020 virus panic, workers were still considered to be working remotely out of “convenience” rather than “necessity”. It should be noted that as of this writing, the case is still active, and the decision could be appealed. In other court cases, the state of New York has ruled that worker’s who could be working in the office with proper accommodations or are hybrid remote fall under the “convenience” category.

When trying to determine whether filing is necessary for a non-resident, out-of-state remote worker, the following flowchart may help:

Conclusion

The complexity surrounding interstate taxation can be complicated, but I hope this primer helps give some clarity. If you feel you could use some assistance with determining the sourcing and filing requirements for your state returns, we are happy to help. You can get the process started by contacting us here.

You can find us at our home website at MageeTax.com

You can check out other blog articles at TacklingFinance.com